You Won’t Believe How Sicily’s Cities Come Alive

Sicily isn’t just beaches and ancient ruins—its urban spaces pulse with life, history, and unexpected charm. I wandered through Palermo’s chaotic markets, stood silent in Syracuse’s sunlit piazzas, and discovered how cities here blend old-world soul with modern rhythm. This is more than travel—it’s connection. If you think you know Sicily, wait until you experience its streets, sounds, and stories up close. The island’s cities are not museum pieces but living, breathing environments where centuries of culture unfold in daily life. From the scent of frying panelle in alleyways to the echo of church bells over sun-bleached stone, every detail tells a story. This journey reveals how Sicily’s urban centers offer a model of resilience, community, and timeless beauty that speaks deeply to those who seek authenticity in travel.

The Heartbeat of Palermo: Where Chaos Meets Character

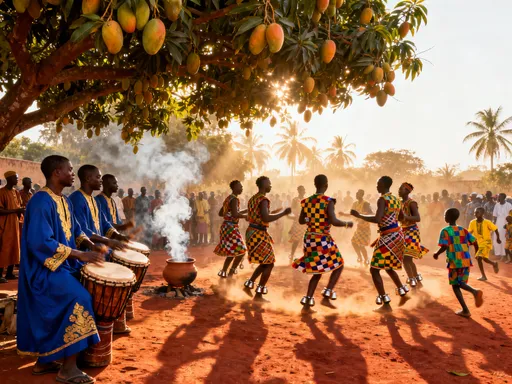

Palermo, the capital of Sicily, does not welcome visitors with polished ease. Instead, it invites with raw energy, a city unafraid of its contradictions. Narrow streets wind like veins through the historic center, where Baroque facades stand shoulder to shoulder with bullet-pocked walls and vibrant street art. The city’s rhythm is set not by clocks but by rituals—men gathering for espresso at 7 a.m., vendors shouting over crates of blood oranges, children chasing each other through shaded piazzas after school. This is a place where urban life feels deeply human, not curated for cameras. The chaos is not disorder but a kind of organized vitality, a testament to a culture that values presence over perfection.

At the core of this energy are Palermo’s historic markets—Ballarò, Vucciria, and Capo—each a microcosm of the city’s soul. Ballarò, stretching across the old Kalsa district, is perhaps the most authentic. Here, local families shop for fresh swordfish, wild fennel, and durum wheat pasta laid out on wooden planks. The air hums with dialect, bargaining, and laughter. Unlike sanitized food halls, these markets are embedded in everyday life, serving residents first and tourists second. The experience is immersive: colors explode from pyramids of tomatoes and lemons, while the scent of fried sfincione lingers in the breeze. These spaces are not attractions—they are lifelines, anchoring communities through shared economy and tradition.

Yet Palermo’s character extends beyond commerce. In neighborhoods like Kalsa, once neglected and now undergoing cultural revival, abandoned buildings are being transformed into art studios, small galleries, and community centers. Local initiatives have repurposed former warehouses into open-air performance spaces, where jazz and traditional Sicilian music blend under starlight. The city’s urban fabric, though scarred by decades of neglect and organized crime, is being gently reawakened through grassroots efforts. Restoration projects emphasize authenticity over gentrification, preserving the texture of lived-in walls and uneven cobblestones. This is not a city trying to become something new—it is remembering who it has always been.

The concept of *passeggiata*—the evening stroll—remains central to Palermo’s social rhythm. As the sun dips behind Monte Pellegrino, families emerge to walk the Via Maqueda or the Foro Italico seafront. Children ride scooters, couples hold hands, elders sit on benches exchanging news. This daily ritual is more than leisure; it is a form of civic engagement, a way of claiming public space and reinforcing bonds. In an age where digital isolation grows, Palermo offers a reminder: cities thrive when they are designed for walking, for lingering, for seeing and being seen. The city’s urban design, though unplanned in the modern sense, fosters connection through proximity, shade, and the occasional gelato stand.

Catania’s Volcanic Pulse: Rebuilding Beauty from Ash

If Palermo pulses with Mediterranean soul, Catania beats with volcanic fire. Built at the foot of Mount Etna, Europe’s most active volcano, the city carries a dual identity—simultaneously threatened and sustained by nature’s power. Its architecture tells this story in black: buildings rise from lava stone, their facades dark and textured, absorbing sunlight like memory. After the devastating earthquake of 1693, much of Catania was rebuilt in the Sicilian Baroque style, using the very material that once buried it. Churches like the Cathedral of Saint Agatha and the Benedictine Monastery stand as monuments to resilience, their ornate details carved from stone born of fire.

The city’s heart is Piazza del Duomo, a grand open space dominated by the elephant fountain—Catania’s symbol—and the cathedral itself. Here, residents gather in the mornings for coffee, students meet between classes, and tourists pause to absorb the scale of history. Unlike more manicured plazas, this space feels lived-in. The cobblestones are uneven, the benches are well-used, and the air carries the scent of roasted almonds from nearby vendors. The piazza is not a stage but a stage for life, where the rhythms of the city unfold without pretense. Urban planning in Catania does not seek to control nature but to coexist with it. Buildings are low-rise, streets are narrow to provide shade, and public fountains offer relief in the summer heat.

Nowhere is Catania’s spirit more vivid than in La Pescheria, the fish market that spills across the port area every morning. More than a place to buy seafood, it is a theater of sensory overload. Fishermen haul in glittering catches of amberjack, red mullet, and cuttlefish, while vendors shout prices in rapid-fire Sicilian. The smell of salt, brine, and lemon is overwhelming, mingling with the cries of gulls overhead. Locals move with purpose, selecting fish with practiced eyes, demanding freshness, exchanging gossip. The market is not for the faint-hearted, but it is honest—a raw, unfiltered expression of daily survival and celebration. It is also a model of sustainability, where supply chains are short, waste is minimal, and relationships between seller and buyer are personal.

Catania’s relationship with Etna shapes more than its architecture and economy—it defines its psyche. Residents speak of the volcano not with fear but with respect, even affection. When Etna rumbles, schools may close, flights may be delayed, but life continues. This acceptance of impermanence fosters a kind of urban flexibility. Buildings are designed to be repaired, not preserved in stasis. Public spaces are adaptable, used for markets one day and festivals the next. The city’s identity is not fixed but fluid, shaped by forces beyond human control. In this, Catania offers a lesson for modern urbanism: resilience is not about resisting change but learning to move with it.

Syracuse’s Timeless Center: Ortygia as Urban Poetry

Ortygia, the ancient island at the heart of Syracuse, feels less like a city and more like a poem written in stone and sea. Connected to the mainland by two bridges, this compact district is a labyrinth of narrow lanes, sun-drenched courtyards, and baroque churches that seem to rise directly from the water. Walking through Ortygia is like stepping into a different dimension, where time slows and senses sharpen. The limestone walls glow amber in the late afternoon, the sea breeze carries the scent of jasmine, and the sound of waves blends with distant accordion music from a street performer. Every turn reveals a new tableau—a hidden garden, a centuries-old well, a vendor selling granita from a bicycle.

The island’s urban fabric is a masterclass in human-scale design. Streets are narrow, often just wide enough for a single car, encouraging walking and cycling. Buildings lean slightly toward each other, creating natural canopies that shield pedestrians from the summer sun. Small piazzas—Piazza Archimede, Piazza Duomo—serve as communal living rooms, where residents gather in the evenings to drink wine, play cards, or simply watch the world pass by. The Cathedral of Syracuse, originally a Greek temple dedicated to Athena, stands as a symbol of layered history. Its columns are still visible within the church walls, a quiet testament to centuries of cultural overlap. This integration of past and present is not forced but organic, a reflection of a city that values continuity over novelty.

Ortygia’s relationship with water is central to its identity. The island is surrounded by the Ionian Sea, and its edges are lined with sea walls where locals swim at dawn and fish in the evenings. Public access to the water is unobstructed, a rarity in many Mediterranean cities where coastlines have been privatized. Children jump from rocks, elders sit on stone benches reading newspapers, and couples walk hand in hand along the promenade. The sea is not a backdrop but a participant in daily life. Even the island’s fountains—like the Fountain of Arethusa—draw fresh water from underground springs that flow directly into the sea, a natural phenomenon that has inspired myths for millennia.

Yet Ortygia is not untouched by modern challenges. Tourism has increased in recent years, bringing economic benefits but also pressures. Some shops now cater exclusively to visitors, selling souvenirs rather than local goods. Rising rents have pushed some residents to the mainland, threatening the island’s social fabric. However, efforts are underway to preserve its authenticity. Local regulations limit short-term rentals, and community groups advocate for maintaining essential services like bakeries, pharmacies, and schools. The goal is not to freeze Ortygia in time but to ensure it remains a place where people live, not just visit. Its magic lies in this balance—a city that welcomes outsiders while staying true to its roots.

Urban Life Beyond the Postcard: Hidden Neighborhoods and Local Realities

While Ortygia, Palermo’s markets, and Catania’s piazza draw the most attention, the true character of Sicily’s cities unfolds in lesser-known neighborhoods. In Siracusa, the Archimede district stretches along the southern coast, a quiet residential area where fishing families have lived for generations. Houses are painted in soft pastels, laundry hangs from balconies, and small boats bob in the harbor. There are no guidebooks here, no souvenir stands—just life as it has been for decades. Children play soccer in the narrow streets, elders gather under awnings to escape the midday heat, and the rhythm of the sea dictates the day’s pace.

Similarly, in Palermo, the Zisa neighborhood offers a different perspective on urban life. Once a royal garden and hunting estate, it has evolved into a working-class district with a strong sense of community. Tree-lined avenues and public parks provide green space in a densely built city, while local associations organize festivals, cooking classes, and youth programs. The Norman Palace of La Zisa, a UNESCO World Heritage site, stands as a reminder of the area’s historical significance, but daily life centers around the neighborhood market and the neighborhood church. These spaces are not tourist attractions but anchors of social cohesion, where generations connect through shared routines and mutual support.

Public transportation in these areas reflects the practical needs of residents. Buses run regularly, though not always on time, connecting suburbs to city centers. Many families rely on scooters or bicycles for short trips, a mode of transport well-suited to narrow streets and limited parking. While infrastructure is not as efficient as in northern European cities, it functions through a combination of formal systems and informal networks—neighbors giving rides, shops holding packages, elders watching over children. This web of informal support is a quiet strength, allowing communities to thrive even with limited resources.

Housing remains a challenge in many Sicilian cities, particularly for young families. Historic buildings, while beautiful, often lack modern insulation, elevators, or accessible layouts. Renovation is costly, and regulations can be complex. Yet, there is a growing movement toward adaptive reuse—turning abandoned warehouses into affordable housing, converting old schools into community centers. These projects are often led by local cooperatives, supported by regional funding, and designed with input from future residents. The emphasis is not on luxury but on livability, ensuring that cities remain inclusive and accessible to all generations.

Design That Breathes: How Sicilian Cities Balance Density and Light

Density in Sicilian cities does not mean overcrowding. Instead, urban design has long prioritized comfort, airflow, and access to light. Traditional buildings feature internal courtyards—*cortili*—that serve as private oases, bringing natural light into the center of thick-walled structures. These spaces are used for laundry, gardening, or family meals, creating micro-environments within the home. In summer, the courtyard’s shade and evaporative cooling from plants and fountains reduce indoor temperatures without air conditioning. This passive design, developed over centuries, remains highly effective today.

Another hallmark of Sicilian architecture is the use of *loggias*—open galleries or balconies enclosed with wood or iron latticework. These semi-outdoor spaces allow residents to sit outside without full exposure to sun or rain, serving as extensions of living rooms. In Ortygia and Palermo, many homes have multiple loggias stacked vertically, creating a layered streetscape where life unfolds at every level. Rooftop terraces are equally important, offering panoramic views and space for drying laundry, growing herbs, or hosting evening gatherings. These features transform vertical space into social and functional assets, making dense neighborhoods feel open and breathable.

Building materials also contribute to thermal comfort. Lava stone in Catania, limestone in Syracuse, and tufa rock in Palermo all have high thermal mass, absorbing heat during the day and releasing it slowly at night. Whitewashed walls reflect sunlight, reducing heat absorption. Windows are often small and deeply recessed, minimizing direct sun while allowing cross-ventilation. These design choices were born of necessity but are now recognized as sustainable solutions in an era of climate change. Modern architects in Sicily increasingly look to these traditions, blending them with contemporary techniques to create energy-efficient buildings that respect local identity.

The result is a form of urbanism that feels dense yet never oppressive. Even in the busiest districts, there are moments of quiet—shaded alleys, hidden courtyards, rooftop gardens. The city does not sprawl endlessly but grows inward, refining and reusing space. This model stands in contrast to car-dependent suburbs, offering a vision of urban life that is compact, walkable, and deeply connected to place. For families and older adults especially, this design supports independence and community, reducing the need for long commutes and isolation.

Markets as Urban Anchors: More Than Just Shopping

In Sicilian cities, markets are not just places to buy food—they are the social and economic heartbeats of neighborhoods. Palermo’s Vucciria, once a chaotic tangle of stalls and neon signs, has undergone revitalization while retaining its soul. By day, it serves locals with fresh produce, cheese, and cured meats; by night, it transforms into an open-air dining scene, where grilled sardines and arancini are shared at communal tables. The market is loud, messy, and alive, a space where generations meet and cultures blend. North African vendors sell spices, Italian grandmothers haggle over eggplant prices, and tourists are welcomed not as spectators but as participants.

Catania’s Fera di a Piscaria operates on a different scale but with the same intensity. Located in the historic port, it is one of the oldest fish markets in Europe, operating daily since the Middle Ages. The energy is electric at dawn, when fishing boats dock and auctions begin. Vendors move quickly, arranging glistening fish on crushed ice, calling out specials in thick dialect. The market is not sanitized—blood stains the floor, nets hang from ceilings, and the smell is unmistakable. But this authenticity is its strength. It supports local fishermen, preserves traditional knowledge, and ensures that seafood reaches tables within hours of being caught.

These markets also serve as intergenerational bridges. Elders teach grandchildren how to select ripe figs or fresh swordfish, passing down culinary wisdom that cannot be found in cookbooks. Young vendors learn the rhythms of supply and demand, the importance of trust, and the value of face-to-face exchange. In an age of online shopping and delivery apps, these spaces uphold a different ethic—one based on relationship, reputation, and reciprocity. They are not just economic engines but cultural repositories, where language, customs, and identity are sustained.

Municipal support has helped preserve and modernize these markets. In Palermo, recent upgrades include better drainage, lighting, and waste management, improving hygiene without sacrificing character. In Syracuse, small grants have helped vendors invest in refrigeration and packaging, allowing them to expand their reach while staying local. These efforts recognize that markets are not relics but vital infrastructure, essential to the health and soul of the city. For visitors, participating in a market is one of the most meaningful ways to connect with Sicilian life—not as observers, but as guests in a long-standing tradition.

The Future of Sicily’s Cities: Preserving Soul While Growing Smarter

Sicily’s cities face real challenges. Tourism, while beneficial, can strain infrastructure and displace residents when not managed carefully. In Ortygia and Palermo’s historic centers, rising rents and the proliferation of short-term rentals threaten to turn vibrant neighborhoods into dormitories for visitors. Aging water and electrical systems require investment, and youth migration to northern Italy or abroad continues to deplete local talent. Yet, there is growing awareness that the solution is not to resist change but to guide it with intention.

Several cities are embracing sustainable urbanism. Pedestrianization projects in Palermo’s historic core have reduced traffic, improved air quality, and revitalized public space. In Catania, new bike lanes and improved bus routes encourage alternatives to car ownership. Adaptive reuse of historic buildings—such as converting old convents into libraries or cultural centers—preserves heritage while meeting modern needs. These efforts are often community-driven, with residents, architects, and local officials collaborating on solutions that prioritize people over profit.

Education and civic engagement are also on the rise. Schools in Syracuse and Palermo now include urban studies in their curricula, teaching students about local history, architecture, and sustainability. Youth-led initiatives promote eco-tourism, urban gardening, and digital storytelling, helping younger generations see value in their hometowns. These programs foster pride and ownership, countering the narrative that opportunity lies only elsewhere.

The future of Sicily’s cities may not be defined by skyscrapers or high-speed transit, but by something more enduring: the ability to live deeply, together. Their model of urbanism—layered, intimate, and rooted in relationship—offers lessons for cities worldwide. In an era of isolation and rapid change, Sicily reminds us that the heart of a city is not in its monuments, but in its markets, piazzas, and quiet courtyards where life unfolds, one conversation at a time.

Sicily’s urban spaces aren’t frozen in time—they’re evolving, breathing entities shaped by centuries of layers. Their magic lies not in perfection but in authenticity, not in grandeur but in grit and grace. To walk these streets is to understand that great cities aren’t built overnight—they grow, adapt, and endure. Maybe the future of urban living isn’t about innovation alone, but remembering how to live deeply, together.