You Won’t Believe What Public Spaces in Komodo Reveal

Komodo, Indonesia, is more than dragons and hiking trails—it’s where public spaces come alive with culture, community, and raw natural beauty. I wandered through harbor docks, village markets, and coastal viewpoints not just as a tourist, but as someone welcomed into daily island life. These shared spaces aren’t just functional—they’re soulful, vibrant, and surprisingly intimate. If you think Komodo is only about wildlife, wait until you experience how people truly live, connect, and thrive in these open-air heartbeats of the island.

Arrival in Labuan Bajo: The Gateway That Feels Like a Living Room

From the moment you step off the plane or ferry into Labuan Bajo, the air carries salt, laughter, and the faint sizzle of grilled fish. This small coastal town, perched at the western tip of Flores Island, serves as the primary gateway to Komodo National Park. But more than just a transit point, Labuan Bajo functions as a communal living room for both locals and travelers. Its waterfront promenade stretches along the bay, a ribbon of concrete and stone where families stroll after dinner, children chase one another between benches, and fishermen sit quietly mending nets as the sun dips below the horizon.

What makes this space so special is not its grandeur, but its authenticity. There are no ticketed entrances or timed visits—just life unfolding in real time. Along the harbor, rows of warungs—simple wooden stalls with plastic chairs—serve steaming bowls of noodle soup, fresh coconut water, and spicy sambal made daily. Locals gather here not because it’s scenic, though it certainly is, but because it’s where they’ve always gathered. The morning brings the fish auction, a lively event where boats unload their night’s catch and vendors bid quickly before the day heats up. By late afternoon, the rhythm shifts: tourists return from diving trips, couples find quiet corners, and music from a distant speaker blends with the lapping waves.

This seamless blend of tourism and daily life sets the tone for the entire Komodo experience. Unlike destinations where visitors are cordoned off in resorts or guided bubbles, Labuan Bajo invites participation. You don’t observe island culture—you step into it. The promenade becomes a stage where everyone, regardless of origin, plays a role. A grandmother selling banana fritters nods to a backpacker taking photos; a group of schoolchildren wave shyly at a foreign family. These small exchanges, repeated across days and visits, build a quiet sense of belonging. And that, perhaps more than any landmark, defines what makes Komodo unforgettable.

The Harbor as a Social Stage: Where Sea Meets Community

The harbor in Labuan Bajo is far more than a docking point for boats—it is a dynamic social stage where work, leisure, and connection unfold in parallel. At any given hour, the docks buzz with activity. Fishermen haul crates of snapper and tuna from wooden vessels, their hands calloused but movements precise. Nearby, tourists lean against railings, cameras poised, capturing the golden light that bathes the water at sunset. Yet these two worlds do not collide—they coexist, each respecting the other’s presence without intrusion.

This harmony stems from thoughtful, organic design. The harbor lacks barriers or signage segregating locals from visitors. Instead, open walkways, scattered seating, and shaded areas encourage lingering. Benches are placed strategically to catch sea breezes, and low lighting extends usability into the evening. As dusk falls, the space transforms. Young couples walk hand in hand, elders sip tea under string lights, and local teens gather near food carts, laughing over shared snacks. It’s common to see a fisherman roll a cigarette while a traveler asks about his day—brief, genuine interactions that reflect mutual respect.

What’s remarkable is how naturally public life unfolds here. There’s no forced programming or curated events—just people using the space as needed. A vendor sets up a folding table to sell fried bananas; a mother brings her toddler to feed seagulls. The lack of rigid rules fosters a sense of ownership among residents and comfort among guests. This balance between utility and sociability is rare in modern urban planning, yet it thrives here through simplicity. The harbor doesn’t need branding or marketing to be effective—it works because it feels lived-in, welcoming, and real.

On the Boats: Floating Public Spaces Between Islands

Travel between Komodo’s islands happens almost exclusively by boat, and these vessels are far more than transportation—they are floating public spaces that foster community among strangers. Most visitors embark on multi-day liveaboard trips aboard traditional phinisi boats, handcrafted wooden sailboats originally built for trade across the Indonesian archipelago. Today, they serve as mobile homes for small groups of travelers, their decks and cabins designed to maximize shared experiences.

Life aboard a phinisi unfolds in rhythm with the sea. Mornings begin with coffee served on the upper deck, where guests gather to watch dolphins leap alongside the bow. Meals are taken at a central table, where conversations flow easily over grilled fish, tropical fruits, and rice. There’s no formal dining schedule—people come and go, sitting beside someone new each time. Evenings often end with storytelling under the stars, as crew members share local legends or fellow travelers recount their favorite moments from the day’s snorkeling or hiking.

The physical layout of these boats reinforces connection. Open-air lounges with cushioned seating face outward, inviting conversation and shared views. Cabins are modest and tucked below deck, ensuring that social life happens in common areas. The crew, typically five to eight members, move seamlessly between roles—cooking, navigating, guiding dives—while maintaining a warm, familial presence. Over three or four days, a temporary community forms, bound not by obligation but by shared wonder and routine. By the final morning, many travelers exchange contact information, surprised by how deeply they’ve connected in such a short time.

These floating spaces demonstrate a powerful truth: well-designed environments can accelerate human bonding. The absence of distractions—no Wi-Fi, no crowds, no urban noise—allows space for presence. The gentle rocking of the boat, the sound of waves, and the rhythm of island time create a meditative backdrop for real interaction. In an age of digital isolation, the phinisi experience offers a quiet reminder of how meaningful shared physical space can be.

Komodo National Park’s Viewpoints: Nature’s Public Squares

Within Komodo National Park, nature itself provides some of the most profound public spaces on Earth. Unlike man-made plazas or parks, these are naturally formed gathering spots—hilltops, cliffs, and elevated trails where visitors pause to absorb the staggering beauty of the landscape. Two of the most iconic are Bukit Cinta (Love Hill) and the Padar Island viewpoint, each offering panoramic vistas that draw people from across the globe.

Bukit Cinta, located on Komodo Island, rewards a moderate uphill hike with a sweeping view of the coastline—turquoise waters, white sand beaches, and rugged hills rolling into the distance. The trail is well-marked and maintained, with rest stops shaded by native trees. At the top, a simple wooden platform accommodates dozens of visitors at once. Despite the number of people, the atmosphere remains peaceful. There are no loud conversations, no pushy photographers—just a shared silence, broken only by the wind and occasional whispers of awe.

Similarly, the Padar Island viewpoint requires a steeper climb, but the payoff is unparalleled: a triple-bay vista that looks like something painted by hand. From this height, the curvature of the Earth seems visible, and the colors shift with the light—blue to green to gold as the sun moves across the sky. Rangers monitor the site to ensure conservation, but they do so with quiet authority, offering information rather than restrictions. Trail design plays a crucial role: one-way paths prevent congestion, and viewing platforms are spaced to allow personal space without isolation.

These natural squares function differently than urban plazas, yet they fulfill the same human need—to gather, reflect, and feel part of something larger. The absence of commercial activity enhances the experience. There are no souvenir stands, no loudspeakers, no entry fees beyond the park permit. What exists is pure: earth, sky, sea, and the quiet camaraderie of strangers united by wonder. In that stillness, a unique kind of connection emerges—one not based on words, but on shared presence in a sacred landscape.

Village Courtyards and Beach Clearings: Hidden Social Spots Off the Beaten Path

Beyond the tourist trails lie the quiet heartbeats of Komodo’s communities—village courtyards, open fields, and shaded beach clearings where daily life unfolds away from the spotlight. Places like Komodo Village on Rinca Island or the small settlement of Papagaran on Komodo Island offer glimpses into a way of life that remains deeply rooted in tradition and environment. These spaces are not designed for visitors, yet they welcome those who approach with respect.

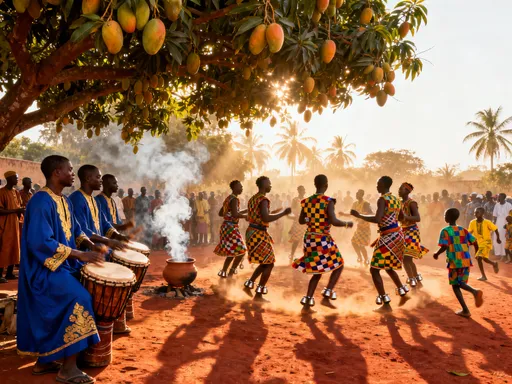

In Komodo Village, a central courtyard shaded by tall palm trees serves as a hub for morning meetings, fishing preparations, and afternoon rest. Men gather here before heading out to sea, checking nets and sharing news. Women sit nearby, weaving baskets or preparing meals over open fires. Children play barefoot in the sand, chasing chickens or practicing traditional dances. There are no benches or pavilions—just natural shade and the soft earth underfoot. Yet the space functions perfectly, shaped by generations of use.

Beach clearings serve a similar role. On Papagaran, a small strip of sand doubles as a docking point and social zone. At low tide, families gather to collect shellfish, while elders sit on logs, watching the water. During festivals or religious events, these areas transform into celebration grounds, with music, food, and communal prayer. The lack of infrastructure—no electricity, no permanent structures—does not diminish their importance. On the contrary, it enhances their authenticity. These spaces are unpolished, uncommercialized, and deeply local.

For travelers fortunate enough to visit, the experience is humbling. There are no guided tours, no entry fees, and no expectations. Interaction happens organically—a smile, a shared fruit, a gesture of thanks. In these moments, the distinction between visitor and resident softens. You’re not observing culture—you’re briefly part of it. And that fleeting inclusion is one of the rarest and most precious gifts of travel.

Markets and Morning Hubs: Where Culture Circulates Freely

Markets in and around Komodo are not merely places to buy goods—they are living networks where culture, economy, and social life intersect. In Labuan Bajo, small morning markets spring up near the harbor, where vendors sell fresh coconuts, grilled corn, handmade snacks, and woven crafts. These are not tourist bazaars with mass-produced trinkets, but genuine community hubs where locals shop and socialize.

One such market, tucked behind a row of warungs, operates only from dawn until mid-morning. Here, fishermen’s wives sell surplus catch—octopus, squid, and small reef fish—arranged neatly on banana leaves. Nearby, an elderly woman offers tuak, a mildly fermented palm drink, in reused glass jars. Transactions are simple, often conducted with a nod or a few soft words. There’s no haggling, no pressure—just exchange rooted in trust and familiarity.

What makes these markets thrive as public spaces is their openness and accessibility. Stalls are low to the ground, allowing easy browsing. Seating is informal—upturned crates or mats on the dirt—but people linger anyway, sipping drinks and chatting. Unlike sterile shopping centers, these markets buzz with sensory richness: the smell of grilled fish, the sound of chopping knives, the warmth of the early sun. They are also inclusive. Children run freely, dogs nap in shaded corners, and elders rest on stools, observing the flow of life.

Even on Rinca Island, near the ranger station, a small vendor area allows local women to sell souvenirs directly to visitors. The items—hand-painted fans, beaded keychains, carved wooden animals—are modest in price but rich in meaning. Buying one isn’t just a transaction; it’s a gesture of appreciation. The vendor might smile, offer a blessing, or share a brief story. These moments, small as they seem, are the threads that weave connection across cultures. In a world increasingly dominated by digital commerce, these markets stand as a testament to the enduring power of face-to-face exchange.

Design Lessons from Komodo: What Makes a Public Space Truly Work?

The public spaces of Komodo offer quiet but powerful lessons in design—one that prioritizes people over profit, simplicity over spectacle, and connection over control. Unlike many modern urban environments, where public areas are heavily regulated, commercialized, or isolated from nature, Komodo’s shared spaces thrive on their lack of complexity. There are few rules, no entry barriers, and minimal signage. Instead, function emerges organically from human need and environmental context.

One key factor is comfort. Shade, seating, and access to water are consistently present, whether in the form of palm trees, wooden benches, or coconut vendors. Safety is ensured not by surveillance or enforcement, but by constant use—these spaces are occupied throughout the day, creating a natural sense of security. Cultural relevance is equally important. Every element, from the layout of a village courtyard to the placement of a fishing net rack, reflects local traditions and daily rhythms. Nothing feels imposed or artificial.

Another lesson is flow. Movement between spaces is seamless—there are no fences or gates separating the harbor from the market, or the beach from the village. Nature and human activity intermingle freely. A path leads from a home to a fishing spot; a trail connects a viewpoint to a resting pavilion. This continuity encourages exploration and spontaneous interaction. People move at their own pace, stopping where they please, staying as long as they like.

Perhaps most importantly, these spaces are inclusive by default. They welcome children, elders, tourists, and residents alike. There’s no admission fee, no dress code, no expectation of consumption. You can sit and do nothing, and still belong. In contrast to many global cities where public areas are increasingly privatized or policed, Komodo demonstrates that the most successful spaces are those that trust people to use them wisely. They don’t need to be grand to be meaningful—they just need to be open.

Urban planners, architects, and community leaders around the world could learn from Komodo’s example. Great public spaces aren’t built with expensive materials or flashy designs. They emerge when we prioritize human connection, respect local culture, and allow room for life to unfold naturally. In Komodo, this philosophy isn’t taught—it’s lived, every day, in every shared smile, every quiet moment on the dock, every sunset watched side by side.

Komodo’s magic isn’t just in its legends or landscapes—it lives in the spaces where people gather without pretense. From harbors to hilltops, these public areas invite participation, not just observation. They remind us that travel is most meaningful when we step into the rhythm of real life. The next time you plan a trip, ask not only where to go—but how you’ll connect once you’re there.